Refining Software Algorithms to Hardware Implementations: Recursion

As a new way of describing hardware programmatically, ROHD opens up the world of hardware design to people with background in software algorithms. Today, we see a lot of hardware design in the space of hardware accelerators which are being used to speed up algorithms that already exist in software. It is therefore interesting to consider design patterns that help us transform traditional software techniques into hardware: a key software technique to consider is recursion which is often the most natural way to describe a given computation.

Trees are a key data structure in both software and hardware upon which recursive algorithms can operate to achieve fast computation. Yet it is challenging to write recursive tree computation in traditional hardware description languages. We will consider a simple recursive algorithm and then a more general hardware tree generator as two techniques for capturing recursive computation easily in hardware using ROHD.

A Pseudo-LRU Algorithm

Set-associative caching requires a replacement policy to figure out which ‘way’ in the cache from which to evict data in order to store new data. Least Recently Used (LRU) algorithms require a very complex history mechanism to compute exactly, so an approximation is often used called ‘pseudo-LRU’.

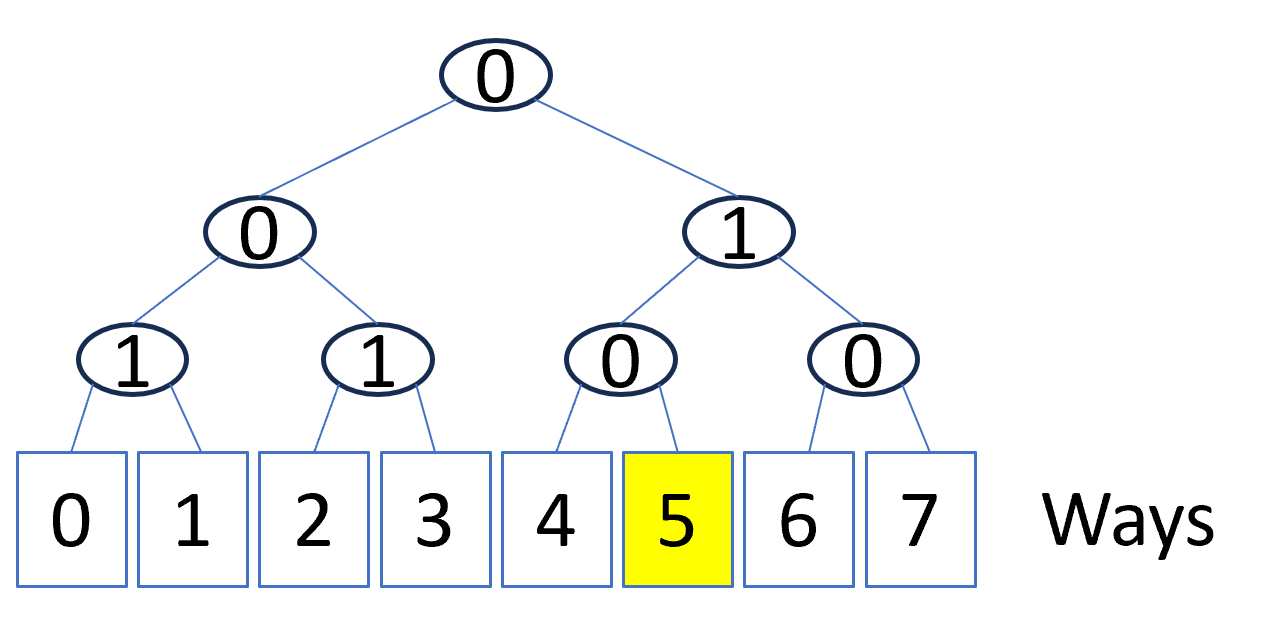

To compute the least-recently-used ‘way’, a pseudo-LRU algorithm uses a binary tree with ‘ways’ as leaves, where a ‘0’ at an intermediate node indicates the LRU ‘way’ is to the right and a ‘1’ indicates it is to the left. In the figure below, we can see that ‘way’ ‘5’ is LRU according to the current settings at each node of the tree.

Two routines are needed to maintain the PLRU tree above in order to do

pseudo-LRU computation, first for finding the LRU way to ‘allocate’ a

new entry and a second for updating the LRU state as ways are ‘hit’

by reads or writes.

PLRU Allocation

Software PLRU Allocation

It is quite natural to describe allocation in the PLRU tree as a

recursive routine. Let us assume the PLRU tree is represented as a 0/1

state vector of the tree nodes as seen from left-to-right. In the

example above, the state vector would be [1,0,1,0,0,1,0]. Below is the

routine written in software that, given the state of the PLRU tree as

a List, returns the integer LRU way.

1 int allocPLRU(List<int> v, {int base = 0}) {

2 final mid = v.length ~/ 2;

3 return v.length == 1

4 ? v[0] == 1

5 ? base

6 : base + 1

7 : v[mid] == 1

8 ? allocPLRU(v.sublist(0, mid), base: base)

9 : allocPLRU(v.sublist(mid + 1, v.length), base: mid + 1 + base);

10 }

Here you can see that the recursion splits on the middle element of the List

at line 7, searching left for the LRU if the node has a ‘1’ otherwise searching

right. At the leaf (line 4) if the node is ‘1’ it returns the left element,

otherwise the right, as the LRU way.

Hardware PLRU Allocation

To implement a tree-based algorithm like PLRU allocation in traditional HDLs, a designer usually has to encode the tree and write a decoder, limited to a specific number of ways. This is not unlike when software developers had to write assembly – using a bit-level abstraction in which to embed algorithms in either software or hardware is painful and error-prone.

Here is an example in Verilog HDL for a fixed 8-way allocation. It is very hard to determine this algorithm is correct as this description obfuscates the algorithm almost completely. Looking at this code a designer would likely wish this to be compiled from a higher level description than have to write and maintain this kind of bit-level code (there could easily be an error in this code that cannot be seen without exhaustive testing of what is an approximate algorithm!).

always_comb begin

if (plru_bits[0] == 0) begin

if (plru_bits[2] == 0) begin

if (plru_bits[6] == 0) lru_way = 3'b111;

else lru_way = 3'b110;

end else begin

if (plru_bits[5] == 0) lru_way = 3'b101;

else lru_way = 3'b100;

end

end else begin

if (plru_bits[1] == 0) begin

if (plru_bits[4] == 0) lru_way = 3'b011;

else lru_way = 3'b010;

end else begin

if (plru_bits[3] == 0) lru_way = 3'b001;

else lru_way = 3'b000;

end

end

end

ROHD Recursive Hardware PLRU Allocation

ROHD allows us to describe the LRU allocation algorithm recursively in hardware as well because it enables us to generate hardware recursively for a PLRU tree of an arbitrary number of ways.

In the hardware algorithm below, we see that we pass in a bitvector in the form

of Logic and again split on the middle element of the vector (line 5 below).

Instead of a ternary operation (lines 4-6 of the software algorithm above), we

can use a multiplexor or mux (line 8 below) on the middle element value to

return the result of the left recursion or right recursion. At the leaf (line

7), we can mux on the node to return the left element in case of a ‘1’

otherwise the right element.

1 Logic allocPLRU(Logic v, {int base = 0, int sz = 0}) {

2 final lsz = sz == 0 ? log2Ceil(v.width) : sz;

3 Logic convertInt(int i) => Const(i, width: lsz);

4

5 final mid = v.width ~/ 2;

6 return v.width == 1

7 ? mux(v[0], convertInt(base), convertInt(base + 1))

8 : mux(

9 v[mid],

10 allocPLRU(v.slice(mid - 1, 0), base: base, sz: lsz),

11 allocPLRU(v.getRange(mid + 1),

12 base: mid + 1 + base, sz: lsz));

13 }

This algorithm is incredibly similar to the software recursive algorithm, replacing conditionals with muxes.

PLRU Hit/Invalidate

A second algorithm needed to maintain the PLRU tree is managing ‘hits’ to a

given way, making that way ‘recently used’, or to manage ‘invalidates’ of a

way, making it available for use and marking it as LRU. Given a way to hit

or invalidate, this algorithm needs to update the state of the PLRU tree and

return that state vector.

Software PLRU Hit/Invalidate

For the software form of the hit algorithm, the PLRU state is again traversed

recursively, splitting on the middle element (line 6) and processing the lower

(line 9) and upper (line 12) portions of the state vector. If the way being

hit is in the left portion, then that portion of the tree is processed,

otherwise it is simply returned as is – similarly for the right.

1 List<int> hitPLRU(List<int> v, int way,

2 {int base = 0, bool invalidate = false}) {

3 if (v.length == 1) {

4 return [if ((way == base) == invalidate) 1 else 0];

5 } else {

6 final mid = v.length ~/ 2;

7 var lower = v.sublist(0, mid);

8 var upper = v.sublist(mid + 1, v.length);

9 lower = (way <= mid + base)

10 ? hitPLRU(lower, way, base: base, invalidate: invalidate)

11 : lower;

12 upper = (way > mid + base)

13 ? hitPLRU(upper, way, base: mid + base + 1, invalidate: invalidate)

14 : upper;

15 final midVal = ((way <= mid + base) == invalidate) ? 1 : 0;

16 return [...lower, midVal, ...upper];

17 }

18 }

Let’s consider the ‘hit’ case where invalidate=false, so we are marking the

way as recently used. At the splitting point, the middle value (line 15) is

set to ‘1’ if the way is to the right of middle, otherwise it is

set to ‘0’, indicating the LRU is in the opposite direction of the hit way.

The leaf processing code (line 4) is similar: if we match the way at the node,

then set the node to ‘0’ to switch LRU away from this leaf, otherwise set to ‘1’

(remember ‘0’ indicates the LRU direction is to the right).

If we consider the invalidate=true case, where we are marking the way as

available or LRU, the logic is simply reversed: a hit means LRU is going in the

same direction of the hit way and wherever we would have set a ‘0’ for a

‘hit’, we would set a ‘1’ instead to invalidate and a ‘1’ instead of a ‘0’.

Invalidate marks each node along the path to the invalidated way with a ‘0’ to

designate the way as LRU.

ROHD Recursive Hardware PLRU Hit/Invalidate

The hardware recursion for PLRU hit/invalidate follows the same pattern as

software. Yet because we need to pass back the entire state vector, not knowing

the actual value of way at generation time, we need to fully process each

element of the vector with the Logic signal way in the recursion. That can

be seen most clearly in the lower and upper recursions (lines 13 and 14) where

we must invoke the recursive routine to pass the way for both. Thes makes

the way signal available at each node to be compared appropriately in

hardware since way is a dynamic signal that changes value after hardware

generation. Remember that in the software algorithm we knew the value of way

so we could just recurse into the appropriate subtree and return the other subtree unprocessed.

1 Logic hitPLRU(Logic v, Logic way,

2 {int base = 0, Logic? invalidate}) {

3 Logic convertInt(int i) => Const(i, width: way.width);

4

5 invalidate ??= Const(0);

6 if (v.width == 1) {

7 return mux(way.eq(convertInt(base)), invalidate,

8 mux(way.eq(convertInt(base + 1)), ~invalidate, v[0]));

9 } else {

10 final mid = v.width ~/ 2;

11 var lower = v.slice(mid - 1, 0);

12 var upper = v.getRange(mid + 1);

13 lower = hitPLRU(lower, way, base: base, invalidate: invalidate);

14 upper = hitPLRU(upper, way, base: mid + base + 1, invalidate: invalidate);

15 final midVal = mux(

16 way.lt(convertInt(base)) | way.gt(convertInt(base + v.width)),

17 v[mid],

18 mux(way.lte(convertInt(mid + base)), invalidate, ~invalidate));

19 return [lower, midVal, upper].rswizzle();

20 }

21 }

At the current node, we compare the way to the range of the current

subtree. If the way is not in range (line 16), we simply return the midpoint

value (line 17) unchanged. This is an example where hardware recursion differs

from software in that we need to check this condition.

At line 18, we can see that when the way falls within this subtree and when

processing the ‘hit’ case (invalidate=false), we return ‘1’ if the way is

in the right subtree and ‘0’ otherwise. Finally, we return a concatenation of

the computed PLRU state vector (line 19). Note that the invalidate=true case

simply reverses the meaning of ‘1’ and ‘0’.

We can see that maintaining a PLRU tree to support pseudo-LRU computation is quite similar in both software and hardware recursive forms. ROHD makes it simple to follow software patterns to generate hardware when the computation is easily described recursively.

A Reduction Tree Component

A parallel reduction is an efficient arrangement of computation of associative operations (like sum or maximum) to compute a single result from an array of inputs.

Reductions are common in both software and hardware and improve the latency of computation logarithmically by arranging a tree of computation to perform parallel operations even when the output is a single result.

In Hardware Description Languages (HDL)s, there is even operator

syntax to perform common bit-wise reductions like or-reduction and

and-reduction. It is more difficult to describe reductions on

complex inputs or operations in traditional HDLs.

Yet in software, more complex reduction trees are possible because of

the compositional nature of software languages. For example the C++

Standard Template Library (STL) contains a template operator

std::reduce to perform reduction generically on STL

containers. Indeed, these operations are threaded to ensure fastest

possible execution in reduction tree arrangements within STL.

To perform more complex reductions in hardware, the ROHD Hardware Component

Library (HCL) provides a ReductionTree

component which takes an associative operation and populates a hardware tree

arrangement to compute a hardware reduction with a latency that is logarithmic

with the number of inputs. In hardware we need to consider pipelining as well

for a reduction of significant length.

Add Reduction Tree

Here is a simple example of a reduction tree using the native add operations of SystemVerilog, but written using a ROHD generator class.

The method addReduce is an operation to be instantiated by the

reduction tree generator. In this case it is simply a native addition

of two inputs, but could be a more complex generator or Module

instance of an associative 2-input computation. Because the tree can

handle lengths that are not powers of 2, the operation must take care

of the length=1 case when the tree is not balanced perfectly.

Logic addReduce(List<Logic> inputs,

{int depth, Logic? control, String name = ''}) =>

inputs.length < 2 ? inputs[0] : inputs[0] + inputs[1];

Then we pass this reduction operation during an instantiation of

ReductionTree, producing a binary tree with 79 13-bit inputs and a tree of

adders (inserted at each node by the addReduce method), along with adding

pipelining at every other level of the tree, starting from the leaves.

main () {

const width = 13;

const length = 79;

final clk = Logic();

final vec = <Logic>[];

final reductionTree = ReductionTree(

vec, addReduce, clk: clk, depthBetweenFlops: 2);

}

It is quite simple to do other operations like max or min or operate on

other datatypes like FloatingPoint or FixedPoint replacing the operator

addReduce with more complex hardware generators, including Module instances.

The ReductionTree can also manage data widening and sign extension for

arithmetic operation reductions.

Mux Reduction Tree

Here is a more complex example (similar to, but not technically reduction) that

passes in a control line that can be indexed by the depth of the tree to perform

a multiplexing (or ‘mux’ing) operation, an operation quite useful in hardware.

Here you see the operation is now the muxReduce method which injects a mux at

each node of the tree.

Note that the ReductionTree component does not know apriori what the node

hardware will be, giving it infinite extensibility.

main() {

const length = 1024;

final width = log2Ceil(length);

final clk = Logic();

final vec = <Logic>[];

final control = Logic(width: log2Ceil(vec.length)));

Logic muxReduce(List<Logic> inputs,

{int depth, Logic? control, String name = 'mux'}) =>

mux(control![depth], inputs[1], inputs[0]);

final muxTree = ReductionTree(vec, muxReduce,

clk: clk, depthBetweenFlops: 2, control: control, name: 'mux');

}

Being able to quickly generate tree computations is another way to map what are common software design patterns into hardware with a high degree of control over the performance of that hardware.