SYCL Native CPU Pipeline Overview¶

Introduction¶

This document serves to introduce users to the Native CPU compiler pipeline. The

compiler pipeline performs several key transformations over several phases that

can be difficult to understand for new users. The pipeline is constructed and

run in llvm::sycl::utils::addSYCLNativeCPUBackendPasses. All of the compiler

pipeline code can be found under

llvm/lib/SYCLNativeCPUUtils,

with the code which originated from the oneAPI Construction

Kit, under

compiler_passes in that directory.

Objective and Execution Model¶

The compiler pipeline’s objective is to compile incoming LLVM IR modules containing one or more kernel functions to object code ready for execution when invoked by the host-side runtime. The assumptions placed on the input and output kernels is as follows:

The original kernel is assumed to adhere to an implicit SIMT execution model; it runs once per each work-item in an NDRange.

It is passed a state struct which contains information about the scheduling.

All builtins which do not relate to scheduling have been processed and we are left with some scheduling related calls to “mux builtins”.

The final compiled kernel is assumed to be invoked from the host-side runtime once per work-group in the NDRange.

The inner-most function is the original input kernel, which is wrapped by new functions in successive phases, until it is ready in a form to be executed by the Native CPU driver.

The WorkItemLoopsPass is the key pass which makes some of the implicit parallelism explicit. By introducing work-item loops around each kernel function, the new kernel entry point now runs on every work-group in an NDRange.

Compiler Pipeline Overview¶

With the overall execution model established, we can start to dive deeper into the key phases of the compilation pipeline.

InputIR

Handling SpecConstants

Adding Metadata / Attributes

Vectorization

Work item loops and barriers

Define builtins and tidy up.

Input IR¶

The program begins as an LLVM module. Kernels in the module are assumed to obey a SIMT programming model, as described earlier in Objective & Execution Model.

Simple fix-up passes take place at this stage: the IR is massaged to

conform to specifications or to fix known deficiencies in earlier

representations. The input IR at this point will contains special

builtins, called mux builtins for ndrange or subgroup

style operations e.g. mux_get_global_id. Many of these

later passes will refer to these mux builtins.

Adding Metadata/Attributes¶

Native CPU IR metadata and attributes are attached to kernels. This information is used by following passes to identify certain aspects of kernels which are not otherwise attainable or representable in LLVM IR.

TransferKernelMetadataPass and EncodeKernelMetadataPass are responsible for adding this information.

Whole Function Vectorization¶

The Vecz whole-function vectorizer is optionally run.

Note that Vecz may perform its own scalarization, depending on the options passed to it, potentially undoing the work of any previous optimization passes, although it is able to preserve or even widen pre-existing vector operations in many cases.

Work-item Scheduling & Barriers¶

The work-item loops are added to each kernel by the WorkItemLoopsPass.

The kernel execution model changes at this stage to replace some of the implicit parallelism with explicit looping, as described earlier in Objective & Execution Model.

Barrier Scheduling takes place at this stage, as well as Vectorization Scheduling if the vectorizer was run.

Barrier Scheduling¶

The fact that the

WorkItemLoopsPass handles

both work-item loops and barriers can be confusing to newcomers. These two

concepts are in fact linked. Taking the kernel code below, this section will

show how the WorkItemLoopsPass lays out and schedules a kernel’s work-item

loops in the face of barriers.

kernel void foo(global int *a, global int *b) {

// pre barrier code - foo.mux-barrier-region.0()

size_t id = get_global_id(0);

a[id] += 4;

// barrier

barrier(CLK_GLOBAL_MEM_FENCE);

// post barrier code - foo.mux-barrier-region.1()

b[id] += 4;

}

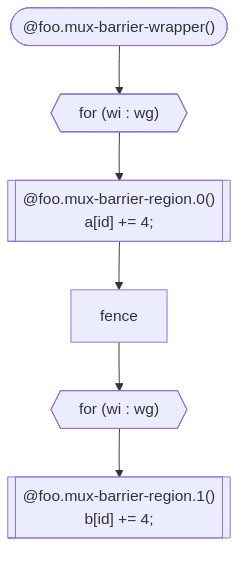

The kernel has one global barrier, and one statement on either side of

it. The WorkItemLoopsPass conceptually breaks down the kernel into

barrier regions, which constitute the code following the control-flow

between all barriers in the kernel. The example above has two regions:

the first contains the call to get_global_id and the read/update/write

of global memory pointed to by a; the second contains the

read/update/write of global memory pointed to by b.

To correctly observe the barrier’s semantics, all work-items in the

work-group need to execute the first barrier region before beginning the

second. Thus the WorkItemLoopsPass produces two sets of work-item

loops to schedule this kernel:

Live Variables¶

Note also that id is a live variable whose lifetime traverses the

barrier. The WorkItemLoopsPass creates a structure of live variables

which are passed between the successive barrier regions, containing data

that needs to be live in future regions.

In this case, however, calls to certain builtins like get_global_id

are treated specially and are materialized anew in each barrier region

where they are used.

Vectorization Scheduling¶

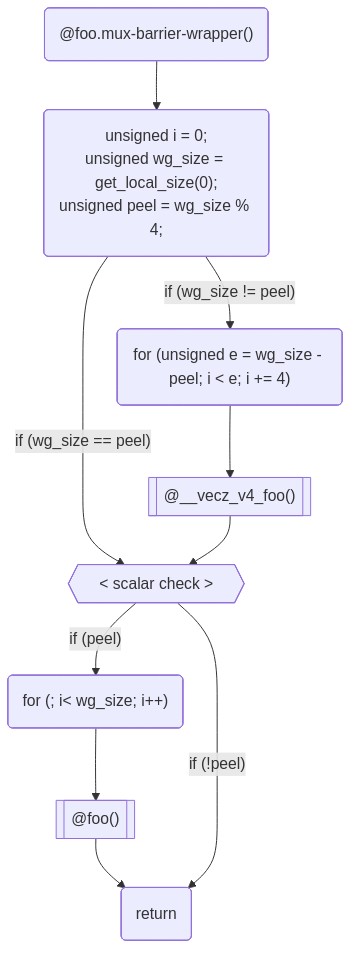

The WorkItemLoopsPass is responsible for laying out kernels which have been vectorized by the Vecz whole-function vectorizer.

The vectorizer creates multiple versions of the original kernel.

Vectorized kernels on their own are generally unable to fulfill

work-group scheduling requirements, as they operate only on a number of

work-items equal to a multiple of the vectorization factor. As such, for

the general case, several kernels must be combined to cover all

work-items in the work-group; the WorkItemLoopsPass is responsible for

this.

The following diagram uses a vectorization width of 4.

For brevity, the diagram below only details in inner-most work-item loops. Most kernels will in reality have 2 outer levels of loops over the full Y and Z work-group dimensions.

In the above example, the vectorized kernel is called to execute as many work-items as possible, up to the largest multiple of the vectorization less than or equal to the work-group size.

In the case that there are work-items remaining (i.e., if the work-group size is not a multiple of 4) then the original scalar kernel is called on the up to 3 remaining work-items. These remaining work-items are typically called the ‘peel’ iterations.

PrepareSYCLNativeCPU Pass¶

This pass will add a pointer to a native_cpu::state struct as kernel argument to all the kernel functions, and it will replace all the uses of SPIRV builtins with the return value of appropriately defined functions, which will read the requested information from the native_cpu::state struct. The native_cpu::state struct is defined in the native_cpu UR adapter and the builtin functions are defined in the native_cpu device library.

For a simple kernel of the form:

auto kern = [=](cl::sycl::id<1> wiID) {

c_ptr[wiID] = a_ptr[wiID] + b_ptr[wiID];

};

with original incoming IR of:

define weak_odr dso_local spir_kernel void @_Z6Sample(ptr noundef align 4 %_arg_c_ptr, ptr noundef align 4 %_arg_a_ptr, ptr noundef align 4 %_arg_b_ptr) local_unnamed_addr #1 comdat !srcloc !74 !kernel_arg_buffer_location !75 !kernel_arg_type !76 !sycl_fixed_targets !49 !sycl_kernel_omit_args !77 {

entry:

%0 = load i64, ptr @__spirv_BuiltInGlobalInvocationId, align 32, !noalias !78

%arrayidx.i = getelementptr inbounds i32, ptr %_arg_a_ptr, i64 %0

%1 = load i32, ptr %arrayidx.i, align 4, !tbaa !72

%arrayidx4.i = getelementptr inbounds i32, ptr %_arg_b_ptr, i64 %0

%2 = load i32, ptr %arrayidx4.i, align 4, !tbaa !72

%add.i = add nsw i32 %1, %2

%cmp.i8.i = icmp ult i64 %0, 2147483648

tail call void @llvm.assume(i1 %cmp.i8.i)

%arrayidx6.i = getelementptr inbounds i32, ptr %_arg_c_ptr, i64 %0

store i32 %add.i, ptr %arrayidx6.i, align 4, !tbaa !72

ret void

}

The resulting IR from a typical kernel with a sycl::range of dimension 1 is:

define weak dso_local void @_Z6Sample.NativeCPUKernel(ptr noundef align 4 %0, ptr noundef align 4 %1, ptr noundef align 4 %2, ptr %3) local_unnamed_addr #3 !srcloc !74 !kernel_arg_buffer_location !75 !kernel_arg_type !76 !sycl_fixed_targets !49 !sycl_kernel_omit_args !77 {

entry:

%ncpu_builtin = call ptr @_Z13get_global_idmP15nativecpu_state(ptr %3)

%4 = load i64, ptr %ncpu_builtin, align 32, !noalias !78

%arrayidx.i = getelementptr inbounds i32, ptr %1, i64 %4

%5 = load i32, ptr %arrayidx.i, align 4, !tbaa !72

%arrayidx4.i = getelementptr inbounds i32, ptr %2, i64 %4

%6 = load i32, ptr %arrayidx4.i, align 4, !tbaa !72

%add.i = add nsw i32 %5, %6

%cmp.i8.i = icmp ult i64 %4, 2147483648

tail call void @llvm.assume(i1 %cmp.i8.i)

%arrayidx6.i = getelementptr inbounds i32, ptr %0, i64 %4

store i32 %add.i, ptr %arrayidx6.i, align 4, !tbaa !72

ret void

}

This (scalar) IR was generated by this pass from the input IR by adding the state struct pointer, substituting the builtins to reference the state struct, and adapt the kernel name.

This pass will also set the correct calling convention for the target, and handle calling convention-related function attributes, allowing to call the kernel from the runtime.

This kernel function is then wrapped again with a subhandler function, which receives the kernel arguments from the SYCL runtime (packed in a vector), unpacks them, and forwards only the used ones to the actual kernel and looks like:

define weak void @_Z6Sample(ptr %0, ptr %1) #4 {

entry:

%2 = getelementptr %0, ptr %0, i64 0

%3 = load ptr, ptr %2, align 8

%4 = getelementptr %0, ptr %0, i64 3

%5 = load ptr, ptr %4, align 8

%6 = getelementptr %0, ptr %0, i64 4

%7 = load ptr, ptr %6, align 8

%8 = getelementptr %0, ptr %0, i64 7

%9 = load ptr, ptr %8, align 8

call void @_ZTS10SimpleVaddIiE.NativeCPUKernel(ptr %3, ptr %5, ptr %7, ptr %9, ptr %1)

ret void

}

As you can see, the subhandler steals the kernel’s function name, and receives two pointer arguments: the first one points to the kernel arguments from the SYCL runtime, and the second one to the nativecpu::state struct.

The subhandler calls the function generated by the WorkItemLoopsPass, which calls the vectorized kernel and the scalar kernel if peeling is needed as described above.

There is also some tidying up at the end such as deleting unused functions or replacing the scalar kernel with the vectorized one.

Any remaining materialization of builtins are handled by

DefineMuxBuiltinsPass,

such as __mux_mem_barrier. The use of this pass should probably be phased

out in preference to doing it all in one place.

Some builtins may rely on others to complete their function. These dependencies are handled transitively.

Pseudo C code:

struct MuxWorkItemInfo { size_t[3] local_ids; ... };

struct MuxWorkGroupInfo { size_t[3] group_ids; ... };

// And this wrapper function

void foo.mux-sched-wrapper(MuxWorkItemInfo *wi, MuxWorkGroupInfo *wg) {

size_t id = __mux_get_global_id(0, wi, wg);

}

// The DefineMuxBuiltinsPass provides the definition

// of __mux_get_global_id:

size_t __mux_get_global_id(uint i, MuxWorkItemInfo *wi, MuxWorkGroupInfo *wg) {

return (__mux_get_group_id(i, wi, wg) * __mux_get_local_size(i, wi, wg)) +

__mux_get_local_id(i, wi, wg) + __mux_get_global_offset(i, wi, wg);

}

// And thus the definition of __mux_get_group_id...

size_t __mux_get_group_id(uint i, MuxWorkItemInfo *wi, MuxWorkGroupInfo *wg) {

return i >= 3 ? 0 : wg->group_ids[i];

}

// and __mux_get_local_id, etc

size_t __mux_get_local_id(uint i, MuxWorkItemInfo *wi, MuxWorkGroupInfo *wg) {

return i >= 3 ? 0 : wi->local_ids[i];

}